One for All and All in One?

Sharon Folkenroth-Hess, M.A., Archivist

Just inside the Delaware Academy of Medicine entrance sits one of the largest objects in our collection. Unlike many of the items on display, visitors can immediately identify its purpose. The wheelchair is synonymous with disability. This association is partly due to the success of the International Symbol of Access (ISA) or ‘Handicap Sign’ as it is colloquially known.

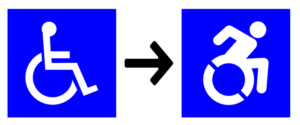

Since its creation in 1968, the blue square overlaid with a white line image of a person in a wheelchair has been used to mark areas of accessibility for wheelchair use. Over time the ISA has been used “shorthand” to mark available access resources, including those that have nothing to do with mobility. This symbol now represents the over twelve percent of Americans living with disabilities even if they do not use a mobility aid(1). After fifty-three years, designers and advocates are pushing for a new symbol. For some, the original is too passive. Others believe it does not accurately represent most people with disabilities.

Those in the first camp are led by the Accessible Icon Project in the US and the Forward Movement in Canada. To them, the current sign is about the chair and not the person in it. If the circular “head” in the image is removed, all that remains is a wheelchair. Both groups revamped the original symbol to make the “person” the focal point and suggests movement. Over the last ten years, stores, hospitals, and other public entities worldwide have adopted the new sign. However, the new symbol is not without controversy. Showing movement implies a level of independence and ability that is not obtainable by some wheelchair users. For them, the new design is not as representative as the original(2).

Representation and inclusion play a major role in other projects seeking to redesign the ISA. In 2018 McCann London, a European marketing firm, developed the Visablity93 campaign to create an open-source suite of invisible disability signs. The name behind the project alludes to the “93%” of people with disabilities that do not use a wheelchair. The firm’s twenty-seven icons depicted ‘invisible’ disabilities like epilepsy and diabetes with a promise to unveil a new IOS icon to replace ISA by the end of 2019(3). While the Visability93 campaign has ended, “invisible disability” advocates continue to fight against the stereotypical image of what a person with a disability looks like. Often non-disabled people see the ISA as a guide for who it is intended to benefit. Advocates argue a new, more inclusive access symbol would represent all people with disabilities and therefore reduce misunderstandings over who is allowed to use these resources.

From 1595, when the first wheeled chair was designed, to the mid-twentieth century, mobility devices were limited to a privileged few. The luxury of mobility that our chair once provided its owner is now recognized as a basic human right by the World Health Organization. Even if the original ISA is changed to become more inclusive, the wheelchair will remain a powerful symbol in the history of disability and accessibility.

- In 2018, an estimated 12.6% of non-institutionalized individuals in the United States reported a disability. Erickson, W., Lee, C., von Schrader, S. (2021). Disability Statistics from the 2018 American Community Survey (ACS). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Yang-Tan Institute (YTI). Retrieved from Cornell University Disability Statistics website: www.disabilitystatistics.org (2021).

- Frost, Natasha. (2018). “The Controversial Process of Redesigning the Wheelchair Symbol.” Atlas Obscura. Retrieved from https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/wheelchair-symbol-redesign (2021).

- Dawood, Sarah. (2018). “Why the wheelchair symbol should be rethought to include ‘invisible disabilities.” Design Week. Retrieved from https://www.designweek.co.uk/issues/30-july-5-august-2018/why-the-wheelchair-symbol-should-be-rethought-to-include-invisible-disabilities/ (2021).

- Invisible Disability Project Mission Statement. Retrieved from https://www.invisibledisabilityproject.org/our-mission/ (2021)