Anthrax in Delaware: A Deadly Legacy

Sharon Folkenroth Hess, M.A., Archivist

The Delaware Academy of Medicine Archives contains hundreds of rare and valuable texts, many of which were printed in Philadelphia and Wilmington. While the information and knowledge found on these pages have saved countless lives, the books themselves have left a deadly legacy in Delaware.

Despite the introduction of clothbound books in the nineteenth century, leather remained a popular material for book covers and spines. Morocco leather, as seen in the image below, is made from goatskin and has a highly visible ‘birdseye’ grain that looks particularly lovely when gilt. This type of leather easily absorbs dyes, allowing for bright blues, greens, and reds. Because of these qualities, morocco was the most popular leather for bookbinding.

By the late nineteenth century, Philadelphia and Wilmington produced four-fifths of the country’s morocco leather output. The twenty-five shops in Philadelphia and the fourteen in Wilmington processed an astounding 125,000 goatskins per day. Importation was essential to supply this industry. Raw or untanned skins came from China, India, Mexico, Russia, Brazil, the Middle East, and North Africa packed in clay, salt, or cured in arsenic.1 Heavy metals were not the only danger present in these shipments; anthrax lay dormant in the dirt, blood, and excrement on these raw materials.

Despite seeing scores of lung infections or “woolsorters’ disease” among people who worked with animal skins and fur throughout the nineteenth century, 1892 stands out as an important year in Delaware anthrax history. That spring marks the first time anthrax was “officially recognized as existing in Delaware” and the start of an epidemic.2 This time the bacteria killed livestock instead of people.

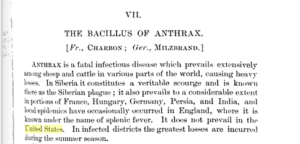

Approximately fifty cows and horses died the first year across nine farms located within a one mile radius near Newport, Delaware.3 The cause of the deaths was identified by the Agricultural Experiment Station in Newark though this diagnosis initially was met with resistance. Dr. George M. Sternberg, the first U.S. bacteriologist, insisted in his 1892 Manual of Bacteriology that anthrax did “not prevail in the United States.”

Anthrax outbreaks on farms were not uncommon in the rest of the world, let alone the United States. By the mid century, German scientist Robert Koch identified the link between specific microorganisms (Bacillus anthracis ) and specific diseases (anthrax). In the early 1880s, Louis Pasteur created a successful two-dose vaccine for animals. European nations had protocols for quarantine and disposal of remains that proved highly effective at restricting the spread.

Working with state veterinarians, the Station campaigned to get farmers to follow similar protocols for cremation of the remains and isolating infected animals. Large amounts of fuel were provided free of charge by a local railroad company for this purpose. Still the carcasses of these unfortunate beasts were either left to rot where they fell, dragged out to a body of water to float away, or buried in a shallow pit. The deaths continued until the autumn chill ended ‘anthrax season.’4

By 1893, the origin of the outbreak was traced to the sale of tannery waste to farmers for use as fertilizer, a practice that began just a few years prior to the outbreak.5 Spores of anthrax lay dormant in the fields in roots and soil. Once animals grazed on the contaminated meadows, death came swift. Bodily fluids from the dead or dying spread the infection to others in the herd. The practice of throwing the bodies in the rivers passed the disease to surrounding farms.

Unlike the year before, only a few cases were reported in early 1893. In August there were zero. Later in the year, however, it was clear that self-interest led affected farmers to suffer losses in silence. On one farm thirty cows out of a herd of forty died. The disease was not recognized by local veterinarians and so the farmer pulled the bodies to the nearby river for burial. Ten infected carcasses floated and were scattered along twelve miles of riverfront. After national assistance was denied, the Station secured state aid to retrieve and burn the cows. All but one were found.6

By 1910, the Station reported that approximately two hundred farms comprising a third of the total area of the state of Delaware were “permanently infected with anthrax.”7 Wash water from local tanneries was still dumped into streams and scraps continued to be sold for fertilizer. Nevertheless, the epidemic officially ended in the fall of 1893.

Vaccines, public education, and effective legislation put a quick end to the deadly ordeal. Doctors from the Experimental Station prepared a two-dose bullion vaccine based on Pasteur’s and developed methods for production and monitoring. Livestock vaccinations were made compulsory at the state’s expense. The failure to report or attempts to conceal outbreaks resulted in hefty fines. More importantly the state offered reparations to farmers for losses provided they received a documented diagnosis of anthrax. Cremation of the carcasses was mandatory.9

Although the anthrax epidemic of 1892-1893 had a happy ending for farmers, tannery workers had to wait until the 1950s for a human anthrax vaccine. In the meantime, those with suspected infections were treated with mercury chloride and forbidden from entering hospitals.

The land under the tanneries is still contaminated with arsenic. The Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development’s Agriculture and Food division reports that while anthrax spores remain viable in soil for 50 years, it will take 200 years for the spores to die out in bones of buried animals. As for the books in our collection? The Smithsonian recommends wearing nitrile gloves and a mask while handling these precious tomes.

TOP IMAGE: courtesy of the Wellcome Library.

- Neale, A. T. (1896). Combating Anthrax in Delaware. Delaware College Agricultural Experiment Station Bulletin, (32), 2.

- Andrews, John B. (1917). Anthrax as an Occupational Disease. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Bulletin, (205), 27.

- Neale, A. T. (1896). Combating Anthrax in Delaware. Delaware College Agricultural Experiment Station Bulletin, (32), 6.

- Neale, A. T. (1896). Combating Anthrax in Delaware. Delaware College Agricultural Experiment Station Bulletin, (32), 9.

- Neale, A. T. (1893). Report of the Delaware College Agricultural Experiment Station for the Year Ending December 31, 1893: Anthrax. Delaware College Agricultural Experiment Station Report, 65.

- Neale, A. T. (1893). Report of the Delaware College Agricultural Experiment Station for the Year Ending December 31, 1893: Anthrax. Delaware College Agricultural Experiment Station Report, 61-62.

- Dawson, Charles F. (1910). Anthrax, Synonyms: Splenic Fever, Malignant Pustule, Woolsorters’ Disease, Milzbrand (German), Charbon (French). Delaware College Agricultural Experiment Station Bulletin (90), 17.

- Neale, A. T. (1893). Report of the Delaware College Agricultural Experiment Station for the Year Ending December 31, 1893: Bacteriological Work. Delaware College Agricultural Experiment Station Report, 115-127.

- Neale, A. T. (1898). Anthrax: A Study of National and of State Legislation on this Subject. Delaware College Agricultural Experiment Station (37), 9-15.